Before his first-pitch fastball hissed toward home plate, Chicago White Sox starter Chad Kuhl held the baseball for an extra beat and took in the beautifully mundane sounds of a back-field spring training scrimmage in Glendale, Ariz., last month. Dugout chatter. Birds chirping. An airplane droning overhead.

Then came the delighted squeal of Kuhl’s 3-year-old son, Hudson, in the stands as his toy monster truck tumbled into the gravel and landed on its roof.

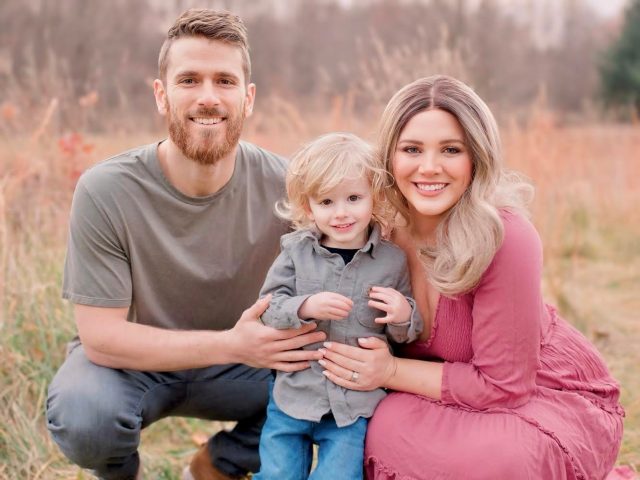

Amanda Kuhl retrieved the truck for her blond-haired boy, then looked back up in time to see her husband strike out the first batter with a back-foot slider.

“I love seeing him back on the field where he belongs,” she said.

They’re all back where they belong — a baseball family together at the ballpark. They missed that. Chad stepped away from the sport last summer as Amanda, his high-school sweetheart, underwent treatment for Stage 3 breast cancer.

Now, Amanda is in the maintenance phase of treatment, her scans showing no sign of disease, and Chad has returned to the mound. After seven seasons with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Colorado Rockies and Washington Nationals, Chad signed a minor-league contract with the White Sox and has started the season with Triple-A Charlotte. The Kuhls are calling this their comeback season — for Chad’s career, for their family.

Early in spring training, Chad stood at his locker in the White Sox clubhouse and smiled as he talked about his new start with the White Sox, about blending old and new to regain what worked earlier in his MLB career, about how much he had missed being in a clubhouse. It’s nice to talk about baseball again, he said. Nice to lose himself in his work and have his family there to watch him.

“It feels normal,” he said, “and it’s pretty incredible for it to feel normal.”

But it’s a new normal. That morning began with Amanda having bloodwork done at their condo in Scottsdale, Ariz., as part of her regular monitoring. That’s not normal. Neither is a double mastectomy at 30. So, normal might be misleading. In the stands later that day, Amanda had another word in mind.

“Boring,” she said, with a laugh. “We welcome boring. Folks have asked what we want out of this season. I’m like, ‘Honestly, a boring season would be lovely.’”

In January 2023, Chad and Amanda were thinking about trying for a second child. Amanda made an appointment with her OB-GYN to discuss the next steps, and it was then that the doctor noticed the minuscule lump. They both shrugged it off as a clogged duct for a breastfeeding mom, but as Amanda drove home, the doctor called and said, “Let’s get it checked out. It’s probably nothing.” Amanda had a mammogram later that day and an MRI biopsy a few days later.

She Googled, waited, and Googled some more.

“That week was living in limbo,” she said. “Once someone tells you it’s there, it’s the only thing you feel.”

The diagnosis was ductal carcinoma — breast cancer. Amanda’s doctors recommended a double mastectomy and lymph node removal to determine the stage of cancer and course of treatment.

Rockies starter Kyle Freeland remembers his wife, Ashley, getting a call from Amanda. The couples grew close during their time together in Colorado and still talk often. But this conversation wasn’t like any of the others. “It was a gut punch,” Freeland said. He picked up his phone and called Chad.

Shortly after the diagnosis, Chad signed a minor-league deal with the Nationals, both because of the opportunity in their rotation and because Washington, D.C., was close to their families in Delaware.

Chad flew to Florida for spring training, and Amanda scheduled surgery for the end of February. She told Chad she would be fine without him; she had family helping with Hudson. But in the days before surgery, as they texted about the logistics, Chad sent Amanda his flight itinerary. He’d be there.

“If it’s possible it was less than a second, she called me less than a second later to yell at me,” Chad later told the Washington Post’s Barry Svrluga.

“I had some words,” Amanda said. “But don’t get me wrong. I was very happy he was there.”

In spring training, Chad drove to the Nationals complex each morning with starter Trevor Williams. They’ve been close since they were both Pirates minor leaguers. On those drives they talked about baseball and their kids, mostly, but some mornings Chad opened up about the fear he felt as Amanda faced cancer. Based on the number of cancerous lymph nodes biopsied, she needed a revision surgery in March. Before starting chemotherapy, she underwent fertility treatments to freeze eggs in hopes of growing their family in the future.

The day of Amanda’s first chemotherapy appointment at Sibley Memorial Hospital in April, Chad was supposed to start for the Nationals. The game was rained out, so he went instead to the hospital. Amanda and Hudson were at Nationals Park the next night for Chad’s start — and, of course, the fireworks show.

“He pitches emotional, but you could tell he was pitching more emotional that night,” Williams said. “He was in a frickin’ hospital room the day before.”

Yesterday, Chad Kuhl drove his wife, Amanda, to her first chemotherapy treatment after recently being diagnosed with breast cancer.

Today, Amanda is at Nats Park watching Chad pitch.

🫶 @RealMrsKuhl 💗 pic.twitter.com/uKwlC1lQ3h

— Washington Nationals (@Nationals) April 29, 2023

When baseball life kept Chad at the ballpark on treatment days, family members swung by to watch Hudson. Other times, the nannies who staff the Nationals’ family room helped. On days when chemo symptoms wore Amanda out, Hudson seemed to sense she needed naps and cuddles.

“Thankfully, we have the world’s easiest toddler,” she said.

“The sweetest, well-tempered little boy,” Chad added.

Amanda, who was Miss Delaware in 2016, has leveraged her social media platform to raise awareness and funds for breast cancer research and nonprofits. She partnered with Nationals Philanthropies, the club’s charitable arm, for a “Cancer Isn’t Kuhl” campaign that benefitted Breast Care for Washington, D.C., and The Previvor. “While she was getting all this care, she was looking out for other people,” Chad said, “which is, in my eyes, pretty amazing.”

For some cancer patients, the diagnosis explains a series of symptoms that had previously puzzled them. Amanda had no symptoms before that appointment last January. “I was very naive,” she said. “I didn’t think breast cancer could truly happen to a healthy 30-year-old.” According to the National Cancer Institute, the odds of a woman being diagnosed with breast cancer in her 30s are 0.49 percent (or 1 in 204).

After extended time away to care for Amanda’s health, the Kuhl family has found solace in returning to their “normal” baseball life. (Courtesy of Nikki Shaw Photography)

It was only after starting to speak publicly about her diagnosis that Amanda heard about others in situations like hers. One of them was Emily Waldon. Waldon, who writes for Baseball America (and formerly The Athletic), was diagnosed with breast cancer at 38 in January 2022. She became someone Amanda went to with questions.

“Regardless of how ugly a season you might be walking through,” Waldon said, “if you get a chance to speak hope or encouragement into the life of someone who is going through something similar, it’s almost like you’re sticking it to cancer: Look, you attacked me, but now I’m going to use my optimism to counter that frustration and fear.”

Waldon, too, had a clear medical history and no symptoms before the cancer diagnosis. Her nurses had a mantra during treatment: Let’s get you back to boring.

While undergoing treatment, Waldon regularly received texts from players, coaches, scouts and media personalities, and she paid that positivity back through Amanda.

“You can’t do it alone,” Waldon said. “For me to play a little part in that for Amanda was incredibly special. Watching her handle her journey with so much grace, and seeing Chad sacrifice his own career to support her, was just an incredible thing to be part of.”

Chad won’t chalk up his lousy numbers with the Nats — an 8.45 ERA in 38 1/3 innings — to the off-field tumult; he was just all out of sorts on the mound. His wife, however, is certain running to chemotherapy appointments and racing after a toddler between starts impacted his performance. “Even if you can turn your brain off, there’s always going to be something going on.”

They agree it was a relief when, after being designated for assignment in June, Chad decided to hang up his spikes for the season. The two of them had met in middle school, and Amanda had been at his side at ballparks in high school, college, the minors and the majors. Now, it was time for them to be home.

Back in Glendale, on that blue-sky day this spring, Chad exited after two scoreless innings and walked over to his family. He sat down beside Hudson — the dad wearing a White Sox jersey, the son in a “Hey Batter Batter” T-shirt and Lightning McQueen Crocs — and they vroomed monster trucks together for a few minutes.

The obsession with monster trucks started this offseason, inadvertently passed down by Williams’ oldest, Ike. When the Williams left for California last fall, they encouraged the Kuhls, who were renting a few blocks away, to stay at their place in Virginia as Amanda continued treatment. Hudson found Ike’s monster trucks and fell in love. (The shark-themed Megalodon that crashed into the gravel is believed to be “borrowed” from Ike’s stash.)

Chad, wife Amanda and son Hudson (pictured) spent time together during Chad’s spring training with the White Sox in Arizona. (Stephen J. Nesbitt / The Athletic)

Chad signed with Chicago knowing Charlotte was his likely starting spot this season. “For me, it’s about the opportunity to prove I can be a big league starter,” he said. “If that means I go to Triple A, I go to Triple A.” Chad appreciated that the White Sox had an interest in him for several years. Former White Sox reliever Liam Hendriks and his wife, Kristi, whom the Kuhls befriended this past year, spoke glowingly of how the organization helped line up Hendriks’ treatment for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Chad has a 3.38 ERA through four starts with Triple-A Charlotte, finding success deploying two “new” pitches, a cutter — his old slider, thrown harder — and a sweeper. The other day, Williams asked Chad to send over video of him pitching this season. Williams liked the spin, velocity and intensity he saw.

“He looks great,” Williams said. “His stuff is so good. He works his ass off, and he’s going to force a team to make a decision: Do we give him a shot at his comeback? I know when he gets that, it’s going to be a tremendous triumph not only for him but for Amanda and their families.”

Chad has an in-season opt-out in his deal with the White Sox, but, for now, he’s just content to pitch.

“When I had that taken away,” Chad said, “I’m like, man, I have a lot of desire to keep playing. I have a lot of hunger, a lot of fire, to keep doing this. … Every decision I’ve made since I was 13 years old — from the time I went to bed, to what I ate, to how I practiced — was to be good at baseball. To miss that was a lot. But I gained a lot more respect for my wife, with what she went through.”

Amanda finished chemotherapy in September and underwent radiation treatment at Sibley Memorial Hospital until early November, a stretch of the offseason in which Chad worked out at Nats bullpen catcher Brandon Snyder’s facility in Manassas, Va. After a couple of months in Delaware, the Kuhls moved into a new home in eastern Pennsylvania, 20 minutes away from both of their parents.

Amanda takes two pills daily that suppress hormones and reduce the chance of cancer recurring, and she receives a hormone-suppressing injection each month. There’s some associated fatigue and nausea, she said, but “nothing is as bad as chemo, or what could have happened without any of this.” She, like Waldon, is passionate about lowering the recommended testing age for breast cancer. The American Cancer Society recommends women between 40 and 44 have the option for a mammogram each year, and that women 45 to 54 have an annual mammogram.

Amanda’s message to others in their 20s and 30s is to visit their doctor each year, write down their extended family’s medical history and do regular self-examinations.

“Know your normal,” she said, “and never think these types of things can’t happen to you — men or women. You don’t know you’re in that blissfully unaware world until it’s too late. I went from not being diagnosed to being diagnosed Stage 3. I went from planning to have baby No. 2 to writing down next-of-kin information.”

She sighed, and continued.

“Be an advocate for yourself.”

Amanda zipped up a backpack that held toys, snacks and a car seat. Getting up to leave, she smiled and said, “Thank you for sharing about our boring life.”

(Top photo: Ashley Landis / AP Photo)